In laboratories and factories across the globe, metal injection molding performs a kind of industrial alchemy, transforming powdered metals and polymer binders into the precise geometries that structure our technological existence. This process, both ancient in its conceptual roots and startlingly modern in its execution, represents something more profound than mere manufacturing—it embodies humanity’s relentless drive to reshape matter according to desire, necessity, and the inexorable demands of capital.

To understand metal injection molding is to peer into the very mechanics of how raw materials become commodities, how elemental substances surrender their natural forms to serve the complex architectures of contemporary life. It is a process that speaks to transformation itself—not merely of metal, but of possibility.

The Grammar of Material Transformation

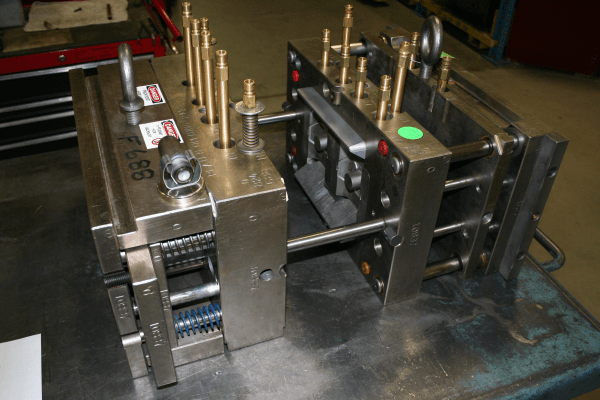

Metal injection molding operates through a syntax of heat, pressure, and time. Fine metal powders—typically ranging from 0.5 to 20 micrometres—are combined with thermoplastic binders to create what industry calls “feedstock.” This mixture, neither fully solid nor liquid, exists in a liminal state that enables its injection into moulds with the precision of plastic yet retains the fundamental properties of metal.

The process unfolds in stages that mirror broader patterns of industrial production: mixing, injection, debinding, and sintering. Each phase demands its own forms of control, its own negotiations between material properties and human intention. The metal powder must surrender to the binder’s embrace, yet maintain its essential metallurgical character. The mould must receive this hybrid substance and shape it without destroying its potential.

Consider what this means: metals that once required casting, machining, or forging can now flow like liquid, fill complex cavities, and emerge as finished components requiring minimal secondary operations. The implications extend far beyond manufacturing efficiency into realms of design possibility and material philosophy.

The Territories of Application

Metal injection molding has colonised industries where traditional manufacturing methods falter against the demands of complexity and precision. In medical devices, components emerge with internal channels and features impossible to machine. In firearms, trigger mechanisms achieve tolerances that ensure safety and performance. In automotive applications, parts integrate multiple functions into single components.

The technology’s reach encompasses:

- Medical implants and surgical instruments: Biocompatible materials shaped to interact with human tissue

- Automotive components: Complex geometries that reduce assembly requirements

- Consumer electronics: Miniaturised parts that enable device functionality

- Aerospace applications: Lightweight yet robust components for extreme environments

- Industrial tooling: Wear-resistant parts designed for demanding production environments

Each application represents a negotiation between material properties, design constraints, and economic pressures. The process democratises complexity, making intricate geometries economically viable at production volumes that would render traditional methods prohibitively expensive.

Singapore’s Strategic Positioning

Singapore has recognised metal injection molding not merely as a manufacturing process but as a strategic capability that reinforces its position in global value chains. The city-state’s approach reflects a sophisticated understanding of how technological capabilities translate into economic advantage.

Dr. Helen Ng, Principal Research Scientist at Singapore’s Institute for Materials Research and Engineering, observes: “Singapore’s investment in metal injection molding represents more than technological adoption—it’s a deliberate strategy to control critical points in the manufacturing value chain. Our capabilities in metal injection molding allow us to serve industries where precision and reliability are non-negotiable, creating dependencies that transcend simple cost considerations.”

This positioning reflects Singapore’s broader industrial strategy: occupying high-value niches where expertise and infrastructure create barriers to competition. The country’s metal injection molding capabilities serve aerospace manufacturers, medical device companies, and electronics producers who require not just components but partnerships based on technical competence and reliability.

The Economics of Material Transformation

Metal injection molding embodies contradictions inherent in contemporary manufacturing. It promises efficiency whilst demanding sophisticated infrastructure. It enables complexity whilst requiring standardisation. It reduces waste whilst increasing energy consumption through high-temperature processing.

The economic logic is compelling for components requiring complex geometries in moderate to high volumes. Traditional machining might waste 70-90% of raw material as chips and shavings. Metal injection molding approaches near-net-shape production, minimising waste whilst achieving tolerances previously requiring secondary operations.

Yet this efficiency comes at a cost measured not merely in capital investment but in environmental impact. The sintering process requires temperatures exceeding 1200°C. The binder systems, often containing polymers, must be removed through careful thermal cycles. The energy intensity raises questions about the true cost of material transformation when environmental externalities are properly accounted.

The Future of Manufactured Matter

As artificial intelligence and advanced sensors enable ever-more-precise control of material properties, metal injection molding evolves beyond simple shape-making into a means of programming matter itself. Gradient materials with varying properties across single components. Embedded sensors that monitor performance in real-time. Multi-material systems that combine metals with ceramics or polymers in single injection cycles.

These developments suggest a future where manufacturing transcends current limitations, where the boundary between design and material properties becomes increasingly fluid. The implications extend beyond industrial production into fundamental questions about the nature of objects, the relationship between form and function, and the ongoing negotiation between human desire and material constraint.

The quiet revolution occurring in factories worldwide represents more than technological advancement—it signals a shift in how humanity relates to matter itself, transforming the ancient dream of alchemy into the quotidian reality of metal injection molding.